Antarctic Region

Things to DO

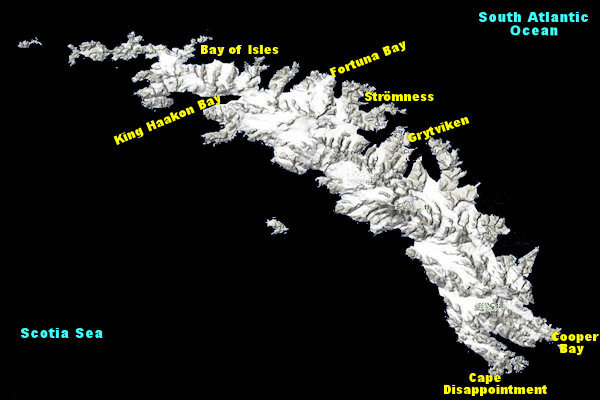

South Georgia

The Island of South Georgia is said to have been first sighted in 1675 by Anthony de la Roché,

a London merchant, and was named Roche Island on a number of early maps.

It was sighted by a commercial Spanish ship named León operating out of Saint-Malo on 28 June or 29 June

1756.

Captain James Cook circumnavigated the island in 1775 and made the first landing. He claimed the

territory for the Kingdom of Great Britain, and named it "the Isle of Georgia" in honour of

King George III.

When Cook's account of South George was published in 1777, his descriptions of fur seals there sett off a

stampede of British sealers, who began arriving in 1786. American sealers followed shortly after, and within

five years there were more than 100 ships in the Southern Ocean taking fur-seal skins and elephant-seal oil.

The British sealer Ann for example took 3.000 barrels of elephant-seal oil and 50.0000 fur-seal skins

from South George in 1792-93.

But this could not last.

By 1831 the american ship Pacific, landing a sealing gang for eight months,

found fur seals scarce. As late as 1909, when the American ship Daisy stayed for five months in what

was probably the last fur-sealing visit to South George, only 170 fur seals could be found.

|

|||||

So complete was the slaughter of South George's fur seals that by the 1930s, the population was pobably at its

lowest extreme, with only about 100 individuals left. In the seven decades that followed, the species made an

astounding recovery. Today there are more than three million fur seals at South George, and in certain seaways,

particularly on the western end of the island, they swim in large herds.

South George whaling began in 1904 when the Compaña Argentina de Pesca, a Norwegian company based in

Buenos Aires, established the first Antarctic whaling station at Grytviken.

Considering the whaling cath during just two of South George's peak seasons it's easy to understand why whales

are so scarce today. In the 1925-26 season, there where five shore stations, one factory ship and 23 whale-

catching ships.

In that season, 1.855 blue whales, 5.709 fin whales, 236 humbacks, 13 sei whales and 12 sperm

whales were caught.

By 1961-62 the Norwegian companies that once dominate the trade, could no longer make a satisfactory profit.

Hoping to make money on frozen meat, Japanese investors took over South George whaling operations the next

season, but soon also found it unprofitable and closed the last shore station, Grytviken in 1965.

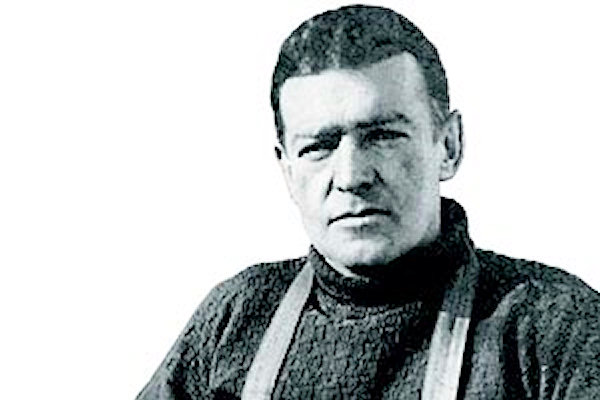

Sir Ernest Shackleton

The Endurance Expedition, is an Antarctic expedition that occurred in 1914-1917. It is generally considered the last major expedition of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, which is characterized by a lack of effective mechanized transport and radio contact with the outside. The expedition failed in its goal of crossing the Antarctic continent by land, but is still famous for the heroic story of survival associated with it.

|

|||||

The Expedition was led by Sir Ernest Shackleton, who in 1908 had set a record of traveling the

furthest south of any expedition. After the conquest of the Pole by Roald Amundsen in 1911, Shackleton

considered crossing the Antarctic to be the last major milestone remaining, and set out in the sailing vessel

Endurance for this purpose. A supporting group, the Ross Sea party, would have the responsibility of laying

supply depots on the opposite end of the continent so that the group would survive the journey from one side

to the other.

Shortly after reaching the Weddell Sea in the Antarctic, on 18 januari 1915, the Endurance became trapped in

pack ice. Shackleton hoped the drifting pack ice would bring the ship to shore, but after nine months of

waiting through the Antarctic winter, on 27 October 1915, encroaching pack ice crushed the ship like an

eggshell.

By this time the men had removed most of the supplies from the ship and had built igloos on the pack ice.

The expedition was now ruined, and the men turned their attention towards survival. With no radio contact, floating on pack ice in the completely uninhabited Antarctic, how were they to get back to civilization?

They decided to leave for nearby islands with known food depots, dragging with them three lifeboats. The men

tried to hike over the pack ice, but it was melting under the heat of the Antarctic summer, causing huge

buckles in the ice up to 10 ft (3 m) in height. In two days of marching, the party only made it two miles.

They decided to set up another camp, Ocean Camp on the pack ice, and kept recovering supplies from the

Endurance, which was nearby, until it finally slipped beneath the ice on 21 november 1915.

|

|||||

The worst was yet to come. Instead of hiking over the ice, the party had to wait for the ice floes to

carry them to where they wanted to be. On 8 April 1916, the ice floe suddenly split, and the men were adrift

with three lifeboats. They journeyed to Elephant Island, at the tip of Graham Land in the northern

Antarctic. After several days of combing the coasts, a narrow rock beach was finally located, and the

lifeboats landed.

30 men were stranded on the small, frozen, rocky island, which was rarely visited by anyone. To get home,

they would need to summon help from South Georgia, a remote whaling outpost 800 miles (1,300 km) across the

Southern Ocean.

On 24 April 1916 Shackleton and 4 men set out in the James Caird (a reinforced lifeboat) across the

Scotia Sea, know as the most perilous and stormy sea on the planet.

On may 10th, they did make it to South Georgia - on King Haakon Bay - the uninhabited south-side of the

island. On may 21 affter a difficult 30-hour hike across the rugged island, which had never been done before, they arrived at the whaling outpost of Strömness.

From there, they traveled to the Falkland Islands to get vessels to pick up the remainder of the men from

Elephant Island. After three failed attempts, Shackleton on 30 August 1916 was finally able to rescue his men

and return home to London. The Imperial Transantarctic Expedition was finally over, having failed in its goal,

but at least every man that participated in it survived the ordeal.

Shackleton died on January 5th 1922, at South Georgia, on his way south for his third Antarctic expedition.

His body was on its way to England when his widow requested to send him back for burial to where he belonged:

in the deep south. He was buried near Grytviken on the 5th March 1922. By tradition now, all visitors to South Georgia visit his grave to pay tribute to the memory of this remarkable man.

Cape Disappointment

|

|||||

After 3 days at sea we finally approached South Georgia from southwest. There was a quite hard wind from

northwest and a big swell as we turned around the south-eastern corner of the island. The spectacular

mountains on South Georgia were visible as we approached and the tops were covered with snow. This place is

know as Cape Disappointment.

It was first charted and so named in 1775 by a British expedition under James Cook, who upon reaching

this position was greatly disappointed in realizing that South Georgia was an island rather than a

continent.

We to, where disappointed, after completely missing the Antarctic Peninsula, South Georgia was our latest

hope for seeing pinguïns etc.

Our expedition-leader told us, that when we will round the island, the weather sould improve, so there is hope.

Cooper Bay

|

|||||

As we rounded Cooper Island the sea suddenly lay calm and the sun was shining.

The day was just perfect for a landing and zodiac cruise in Cooper Bay!

We had lots of time and spent some hours observing a small colony of King Penguins with chicks,

Gentoo Penguins, Snowy Sheathbill, Giant-petrels, Fur Seals and Elephant

Seals, including some males.

Then we walked to the other beach for a closer look at the Macaroni Penguins and after that we went

cruising with the zodiacs to nearby Cooper Island, where there was a large colony of Chinstrap

Penguins.

The South George Pipit is the only songbird in Antarctica. This sparrow-sized bird, lays op to four

eggs in a nest of dried grass among the tussock grass. It has been exterminated from most of South Georgia by

rats and now nests only on offshore islands and along the South Coast.

|

|||||

In the afternoon, we were visited by Ruth from the South Georgia Heritage Trust, who told us about

the ongoing rat eradication programme for South Georgia.

The arrival of rats and other rodents on South Georgia as stowaways on sealing and whaling ships had a

catastrophic effect on the island’s native bird populations. Rats eat the eggs and chicks of many

ground-nesting bird species. As a result, the main island has been all but abandoned by the storm petrels,

prions, diving petrels and blue petrels that once nested there.

As a result of global warming, South Georgia’s glaciers are retreating rapidly – two glacial barriers have

been lost in the last few years alone. Without these barriers, the few remaining rodent-free areas will

quickly be overrun and South Georgia’s remaining bird populations will suffer the consequences.

The first phase of the rat eradication project has just been successfully completed in the sector around

Grytviken, where bait has systematically been spread by two helicopters that have been purchased for the

project. The remaining rat-infested parts of the island will be baited as quickly as possible, sector by

sector, in the years to come.

Various logistical support has been provided by the South Georgia authorities, but the project relies heavily

on private donations.

Grytviken

|

|||||

This morning we found ourselves at anchor off Grytviken and King Edward Point, in calm but

increasingly rainy weather with low clouds covering the mountain tops.

It's South Georgia's only whaling station that can be visited - after all the hazardous material and

dangerous structures were removed by the South Georgia Government. It operated from 1904 to 1965.

When entering the wonderful South Georgia Museum, be sure to look up. Otherwise, you'll miss - as

many do - the mounted Wandering Albatross soaring overhead.

The museum, opened in 1992, is housed in the former station manager's house, built in 1916 by the Norwegians.

It's filled with fascinating exhibits on South Georgia's history and wildlife. The shop sells an amazing

array of clothing, patches, souvenirs, postcards, slid sets and books.

the restored Whaler's church, consecrated on Christmas Day 1913, is a typical Norwegian Church.

Indeed, it was originally erected in Strommen before being dismantled and shipped here.

Inside are memorials to Grytviken's founder Carl Anton Larsen and to Shackleton, whose funaral

was held here.

Strömness

|

|||||

In the afternoon we managed to land at Strömness, another of the former Norwegian stations.

Stromness began as an anchorage for the floating factory ship Fridtjof Nansen II in 1907. A shore

station began operating in 1913, but in 1931 Stromness was converted to a ship repair yard until it closed in

1961. The whale-catcher's propellers on the beach are reminders of Stromness'latter role.

On the beach we where met by rain and wind (that luckily subsided), and by a multitude of Fur Seal pups

playing and barking everywhere on the beach and in the valley.

Small groups of determined Gentoo Penguins waded out of the sea and trotted up a slushy path towards

their breeding grounds a couple hundred metres inland.

In 1925 seven Reindeer were released at Husvik. They were brought from Norway for sport and meat.

The decendants now spread around Stromness Bay. As they have a nagative effect on the vegetation, they will

be shot in the next years.

At night some Black-bellied Storm Petrel's were atracted by the ligt and landed on the ship. They were

released at day-light.

Fortuna Bay

|

|||||

A strong northerly and heavy swell precluded the landings on Prion Island and Salisbury Plain which

were scheduled for today.

So, we headed South towards Fortuna Bay, hoping for shelter and thus calmer conditions. That might

have allowed a landing close to the medium-sized rookery of King Penguins.

With the wind up to 35 knots and a very big swell coming from our beam the voyage south was somewhat

uncomfortable.

We eventually arrived off Fortuna Bay and, with Fur Seals bobbing up and down in the turbulent sea. On

arrival at the usual anchoring spot in sight of the spectacular glacier at the head of the bay, a gleam

of sun in an otherwise overcast sky produced a rainbow auguring well perhaps for a landing.

That was not to be.

Due to hudge crashing breakers on the shore-line, it was decided to cruise slowly up and down to see if, as

forecast, the wind shifted to the west which would give a better chance during the afternoon.

Luck was not with us.